תולדות בית כנסת עמק רפאים – שנים ראשונות

מאת מאיר אדלשטיין, כסלו תשע"ג

נסיבות הקמתו והתפתחותו של בית הכנסת שלנו בשנותיו הראשונות דומות בהיבטים מסוימים למאפיינים בתולדות הקמתה של מדינת ישראל, ולהתפתחותה בשנותיה הראשונות. המתבונן יבחין בקווי דמיון בכל הקשור להתחלות בתנאי סף נחותים, בהתמודדות בלתי פוסקת תוך עקשות ודבקות במטרה בקשיים רבים בכל תחומי החיים כמו בקליטת עולים, בתנאים כלכליים קשים, בהטרוגניות חברתית ותרבותית, במטענים רגשיים נחלת העבר ועוד ועוד.

מהו, אם כן, אותו מיקרוקוסמוס פרטי שלנו, מתפללי בית הכנסת, המזכיר את שנותיה הראשונות של המדינה?

שכונת בקעה עד מלחמת העצמאות

קורותיו של בית הכנסת כרוכים כמובן בהתפתחותה הכללית של שכונת בקעה. השכונה שבתיה הראשונים נבנו כבר במחצית המאה התשע עשרה, היוותה חלק מהתפתחות זעיר אורבנית שהחלה לתפוס אחיזה באזור עמק רפאים (במושבות הגרמנית והיוונית דהיום). מאז ראשית אותה מאה התיישבו באזור בעיקר גרמנים (טמפלרים) ויוונים. ישנן אף עדויות על ניסיונות לרכישת קרקעות על ידי יהודים בראשית המאה העשרים, ניסיונות שלא הטביעו את רישומם בהתפתחות האזור.

ההתפתחות של בקעה היתה הדרגתית, כשבתיה הראשונים נבנו ברחובות שמשון וראובן. בתום מלחמת העולם הראשונה נמנו בה כעשרים בתים, ביניהם המבנה של בית הכנסת שלנו. בהמשך התפתחה מאוד והגיע למימדים המזכירים את ימינו אנו. נראה שהגורם המרכזי להתפתחות זו היה עתודות גדולות של קרקע פוריה לא מיושבת, קרקע שהיוותה מוקד משיכה לערבים נוצרים אמידים, ליוונים ולארמנים, ואף למספר משפחות יהודיות. אלה האחרונות נטשו ברובן בשנת 1929 כנראה בשל מאורעות תרפ"ט. עם זאת, נותרו בשכונה שתי משפחות זלצמן (בעלי מפעל למוצרי מתכת ובכלל אלה קופסאות קק"ל) וכץ. לשכונה נמשכו גם משפחות ידועות בעלות אמצעים כמו היבואן הראשי של מכוניות ביואיק (Buick) במזרח התיכון, שהתגורר במעלה רחוב שמשון, וגם פקידי ממשל בריטים בכירים, וביניהם כנראה גם אדוארד קיטרוטש (Keith-Roach) מושל מחוז ירושלים מטעם ממשלת המנדט (1945-1926), אף הוא רחוב שמשון לפחות בחלק מתקופת כהונתו.

הפריחה והשגשוג נמוגו עם פרוץ מלחמת העצמאות. המשפחות הערביות נמלטו במרוצת המחצית הראשונה של שנת 1948, כשהן מותירות אחריהן בתים מטופחים וגינות פורחות. נותרו בשכונה משפחות נוצריות ממוצא יווני וארמני ושתי המשפחות היהודיות (נשותיהן של שני ראשי המשפחות היו נוצריות).

ימים ראשונים עם קום המדינה

ה"הגנה" שהשתלטה על השכונה, ללא קרב, בשלהי אפריל-תחילת מאי 1948, סגרה אותה לכניסת אזרחים, והכריזה עליה כעל שטח צבאי סגור כנראה משיקולים צבאיים. מלבד כוחות ההגנה והתושבים המעטים שהמשיכו להתגורר בשכונה מימי המנדט, נותר האזור סגור מספר חודשים לכניסת תושבים חדשים. מטבע הדברים שהעזובה החלה נותנת את אותותיה בכול. הבתים הוזנחו ולעתים הושחתו במתכוון, תוך ביזת תכולתם. אביזרים בסיסיים היו חסרים או מנופצים, רשת החשמל נותקה לעתים תכופות, אספקת המים שובשה (רעה חולה בירושלים של אותם ימים) – כל אלה היו תופעות שבשגרה. כך מסכם את רשמיו וולטר איתן, המנכ"ל הראשון של משרד החוץ הישראלי, שביקר אז בבקעה ונכנס לאחד הבתים בשכונה, בלוויית הקונסול האמריקאי הכללי, לבקשתו של זה האחרון: "כל חדר וחדר הושחת כליל… המקום כולו נראה כאילו עדת פראים חלפה דרכו. זו לא היתה רק שאלה של גנבה פשוטה, אלא של הרס מכוון וחסר פשר…"; וזוהי דוגמה אחת מני רבות. העזובה ניכרה גם ברחובות בכל הקשור לתאורה לקויה, לחוטי חשמל קרועים, לתנאי תברואה שרחוקים מלהשביע רצון ולפגעים נוספים.

גלי העליה הגדולים שפקדו את המדינה למן הקמתה, אליהם התווספו אזרחים ותיקים מפוני הרובע היהודי בעיר העתיקה, פקידים של משרדי ממשלה שנאלצו להעתיק את מגוריהם לירושלים ועוד תושבים אחרים – כל אלה אילצו את הממשלה לפתוח את בקעה למגורים מיד בראשית 1949, ואולי אפילו זמן קצר קודם לכן. השכונה התמלאה במהירות בתושבים שהתמקמו בדירות הנטושות. מאחר שמדיניות הממשלה בנושא לא היתה נחרצת דיה, השתלטו תושבים על דירות לעתים אפילו בכוח הזרוע, ויש שפלשו לדירות שכבר התגוררו בהן דיירים. המונח "פלישה" היה נפוץ מאוד באותם ימים, ולעתים נדרשה התערבות המשטרה כדי להשליט סדר. דירות לא מעטות אוכלסו, בסופו של דבר, בשתי משפחות ולעתים אף ביותר. גם עברות רכוש לא חסרו (פגע שתושבי השכונה נפטרו ממנו רק שנים לאחר מכן).

האוכלוסיה היתה הטרוגנית בכל תחום ותחום שרק ניתן להעלות על הדעת: עולים בני עדות המזרח שהחלו להגיע ממדינות ערב ומצפון אפריקה, ולצידם יוצאי מזרח אירופה ומרכזה כשאליהם מתווספים עולים מגרמניה וגם ילידי הארץ. תושבים ממוצא אנגלו-סכסי לא היו בנמצא… בליל שפות ריחף באוויר כשמעל כולן ערבית על ניביה השונים, הונגרית, יידיש ועברית. דומני שבזה הסדר. למותר לציין שכל עדה הביאה עמה את אורחות חייה ומורשתה התרבותית. בקיצור, כור היתוך במלוא מובן המילה שבעבע עוד שנים ארוכות עד שעלה בידו למלא, פחות או יותר, את יעודו.

נסיבות הקמתו של בית הכנסת ושלבים ראשונים בהתפתחותו

לתוך מציאות זו הגיעו ראשוני המתפללים של בית הכנסת שלנו. המייסדים הגיעו ברובם מהונגריה, מצ'כוסלובקיה ומרומניה, אך גם מגרמניה, מפולין ואפילו משפחה אחת ילידת הארץ. על אף המגוון היחסי של ארצות מוצאם, מכנה משותף היה לכולם (כמעט): הם היו ניצולי השואה, שנמלטו מהתופת בעור שיניהם. אחדים מהם עלו לפני פרוץ מלחמת העולם אך רובם לאחר סיומה. כולם הותירו מאחוריהם בני משפחה רבים בגיא ההריגה, שזכרם שכן בלבם כל העת. דומה שזיכרונות השואה והמועקה בלב היו "בני ברית" בבית הכנסת שלנו, וצילם ריחף בחללו עוד שנים ארוכות. היו כאלה שהזיכרונות והמעורבות הרגשית לא הרפו מהם עד יום מותם, כמו למשל דוד (זיגי) שטיינר.

משפחות המייסדים, כעשרים במספר, הגיעו לבקעה אם ממקומות אחרים בעיר ואם מחוצה לה. כמעט כולן, ואפשר שאפילו כולן, היו דלות אמצעים. את דירותיהן הן קיבלו ב"דמי מפתח" מה "רכוש הנטוש" (לימים חברת "עמידר"). ראשי המשפחות עסקו בפקידות (בעיקר במשרד הדתות) אך היו ביניהם גם מורים,עובדי כפיים, שני סופרים, שלושה משפטנים ורופא אחד. ראוי לציין שבחלקם הגדול הם היו יודעי ספר ובני תורה, והיו ביניהם גם תלמידי חכמים של ממש. אף שלא הגיעו לשכונה כמקשה אחת, רבים מהם הכירו זה את זה עוד קודם לכן בארצות מוצאם ו\או במקומות עבודתם בארץ. הגיוני אפוא שהם ביקשו לכונן בית כנסת משלהם. אך היכן? מצוקת הדיור החריפה בשכונה לא פסחה גם על מבני ציבור. הבקשות שנערמו במהלך 1949 על שולחנו של הממונה על מחוז ירושלים במשרד הפנים להקצאת מבנים למוסדות, ובכלל אלה גם לבתי כנסת, הינן עדות לכך. בחודשים הראשונים לבואם לשכונה נאלצו אפוא למצוא מקומות תפילה מכל הבא ליד. מזיכרונות עמומים של מתפללים ראשונים וצאצאיהם עולה שתחילה התפללו בביתו של הגבאי הראשון ברחוב אהוד, ממש בסמוך למבנה הנוכחי.

לעומתם יש הזוכרים כי קודם לכן הם התפללו בבית כנסת אחר ברחוב גדעון, ואפשר שהזיכרונות כולם נכונים. בד בבד היו מביניהם שהמשיכו לנסות ולאתר מבנה פנוי. והנה נקרתה לפניהם ההזדמנות באחד מימות הקיץ. הם הבחינו במקרה במבנה נטוש ונעול ברחוב יעל. לימים נתברר, שהיה זה מבנה ששימש כבית מלאכה ומגורים של מעבד עורות\סנדלר ערבי שנטש את המקום, והותיר מאחוריו מצבור גדול של עורות במרתף ביתו. המבנה אמנם אותר אך כיצד ניתן היה להעבירו לרשותם? הם פנו לממונה על המחוז ב- 26 ליולי 1949 והמתינו לתשובתו. המתינו לתשובתו? יש מקום לסברה שאחדים מהמייסדים (יצחק בנו של אליהו לבנון, שלמה גולדשמידט, משה ליכטנשטיין, ישראל מנחם גנץ) נטלו את החוק ואת היוזמה לידיהם ופרצו פנימה באישון לילה. רק לאחר שהתמקמו במבנה פנו לממונה באותו מכתב שהוזכר קודם כדי לקבל היתר רשמי. במטרה לשוות לפעולה אופי חוקי כלשהוא, שהרי ניתן היה מייד לפנותם, הם העבירו את אחד החדרים (לימים אחד מחדרי עזרת הנשים) למשרד הדתות. המשרד הכניס לחדר ספרי קודש למיניהם, וגם הקצה פינה לסופרי סת"ם להגהה ולתיקון ספרי תורה שהובאו מהקהילות החרבות באירופה. בהקשר לפעילות זו יש לציין במיוחד את אליהו לבנון, עוזר למנכ"ל משרד הדתות (ששניים מבניו, יעקב ומשה, נהרגו אך שנה קודם לכן במלחמת העצמאות), ואת אשר אדלשטיין מנהל המשק והמחסנים של המשרד.

מאידך אפשר לטעון שרק לאחר קבלת אישור הממונה על המחוז נכנסו פנימה. אבל אם כך היו פני הדברים מדוע פרצו פנימה באישון לילה? מכל מקום, מאחר שישנן עדויות רבות בידינו שבליל ראש השנה תש"י (23 בספטמבר 1949) כבר התפללו בבית הכנסת, ניתן לקבוע שבית הכנסת הוקם אי-שם בין סוף יוני למחצית ספטמבר 1949. המבנה תאם, פחות או יותר, לצרכי בית הכנסת בכל הקשור לעזרת הגברים שהיתה מורכבת מאולם מלבני מואר ומרווח. מפליא הדבר שבמרכז הקיר הצפוני נמצאה גומחה ובתוכה ארון עץ עם פיתוחים ששימש כנראה את הדיירים הקודמים. הארון הפך בן לילה, לאחר שינויים זעירים, לארון קודש נאה העונה על הציפיות, ארון שכאילו המתין מזה עשרות שנים לייעודו האמיתי והסופי…

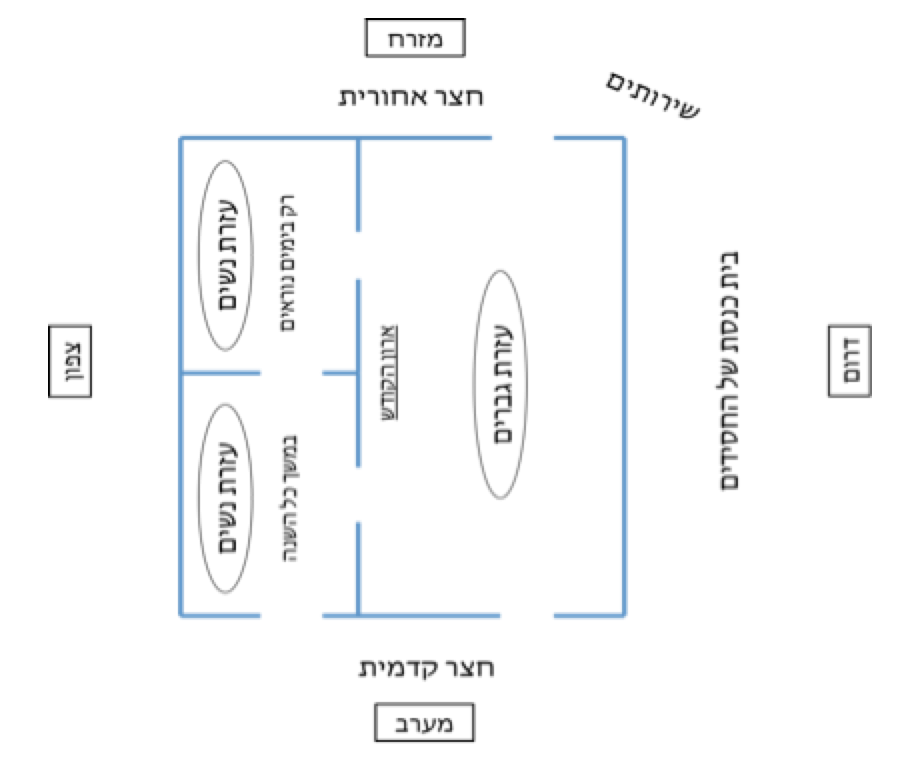

גורלה של עזרת הנשים שפר עליה פחות. לא ניתן היה להקצות מקום מאחורי עזרת הגברים כמקובל, בשל צמידותו של מבנה נוסף (בית הכנסת של החסידים) לקיר הדרומי של בית הכנסת. לפיכך נאלצו למקמה בשני החדרים בקדמת בית הכנסת, מלפני עזרת הגברים בצד צפון. חדרים אלה היו מחוברים ביניהם באמצעות דלת. בכל חדר היה גם פתח נוסף שהוביל לעזרת הגברים. בין שני הפתחים הללו הפריד חלק מהכותל הצפוני שבו ניצב ארון הקודש. בשל מיקומה המוזר, עזרת הנשים היתה רחוקה מלענות על צרכים בסיסיים, במיוחד בגלל שדה ראיה מוגבל מאוד לעזרת הגברים וצפיפות רבה. יש לציין כאן שרק חדר אחד בלבד מבין השנים תפקד כעזרת נשים במשך כול השנה. החדר השני הועמד למגורי משפחת אחד המתפללים שדירתה היתה צמודה למבנה בית הכנסת בצידו הצפוני. חדר זה שימש כעזרת נשים רק בימים הנוראים.

היו גם ליקויים בולטים נוספים: החצר בחזית בית הכנסת היתה מוזנחת ולא מרוצפת. צריך היה להמתין כחמש עשרה שנים נוספות עד ששופצה ורוצפה על ידי משפחת גנץ לזכר אבי המשפחה, ישראל מנחם, שנפטר והוא עדיין במלוא אונו. שירותים (ומטבחון) לא היו למעשה. אמנם היו מעין "ספיחי שירותים" בחצר האחורית של בית הכנסת אך אלה כמעט שלא היו ראויים לשימוש אדם. רק שנים רבות לאחר מכן הותקנו שירותים ברמה סבירה בחצר הקדמית. עד היום מהדהדת באוזני ותיקי בית הכנסת אנחת הרווחה של המתפללים דאז עם התקנת השירותים החדשים. התרשים שלפנינו יקל על המחשת תיאור המבנה בשנים הראשונות:

לאחר הכניסה נתעורר הצורך המידי להתקין את בית הכנסת לתפילה בכול הנוגע להצטיידות בתשמישי קדושה למיניהם וגם בעזרים חומריים. בהיעדר אמצעים כספיים נאלצו המייסדים להשתמש בכושר אלתור ובתעוזה. הריהוט נלקט מכל הבא ליד. כך למשל לצד השימוש בכורסאות אדומות ובספה שנמצאו בתוך המבנה עצמו, הובאו ממחנה אלנבי הסמוך ספסלי אוטובוס ומשאית שפורקו על ידי המתפללים עצמם,ועדיין נותרו מתפללים שנאלצו לעמוד או לשבת על הרצפה במהלך התפילה בשל מחסור במקומות ישיבה. לאחר פרק זמן, כנראה בתחילת שנות החמישים, נרכש "ריהוט בית כנסת" מבית כנסת אחר שהצטייד בריהוט חדש. לבד משינויים קלים, שינויים מהותיים במבנה עצמו הם לא בצעו. למעשה הותירו המייסדים את הפיתוח ואת האסתטיקה לדור הבא, דור שאכן מילא תפקיד זה בצורה מעוררת כבוד. יש להניח שעוד תימצא המסגרת המתאימה לתיאור סאגת השיפוצים של בית הכנסת, שהחלה למעשה בשלהי שנות השמונים של המאה הקודמת ושהניבה בסופו של תהליך את צורת המבנה ואת תכולתו כפי שהם נראים היום.

ההצטיידות בספרי תורה ובספרי קודש נעשתה בצורה קלה יותר. שלושה ספרי תורה קטנים במידותיהם, ששרדו את החורבן, הובאו על ידי שלושה מתפללים (דוד גרינוולד, שלמה (פריץ) גולדשמידט ודוד (זיגי) שטיינר), אליהם נתווסף מאוחר יותר ספר גדול מימדים, אף הוא אוד מוצל מאש, שהובא ממשרד הדתות על ידי אשר אדלשטיין. משרד הדתות דאג גם לחומשים, סידורים, מחזורים וספרי קודש אחרים.

סדרי תפילה ומנהגים

עם כל חשיבותם של התנאים החומריים, הרי שהשאלות הכבדות באמת התמקדו בתחום הרוחני. המייסדים נאלצו להתמודד, באופן מידי, עם שאלות הקשורות לקביעת אופיו של בית הכנסת, איזה תוכן ליצוק בין כתליו, כיצד לבנות את עולם התפילה ומה יהיה אופייה של הקהילה.

מאחר שהמתפללים ביקשו, מטבע הדברים, לשמר את מנהגי אבותיהם, ומכיוון שרוב המייסדים נמנו עם המחנה הציוני-דתי שבמרכז אירופה, הרי שהתפילה וסדריה התנהלו בדרך כלל ברוח המסורות והמנהגים שבארצות ההן. אך היו גם לבטים וחיפושי דרך שהביאו לשינויים. נראה שכבר בתחילה בחרו רוב המייסדים להתפלל בנוסח אשכנז. עם זאת ישנן עדויות שהדבר לא נקבע מיד, ושבאותם ימים ראשונים הש"ץ היה רשאי להתפלל בנוסח שהוא רגיל בו, ובכלל זה בנוסח הגר"א ובנוסח ספרד. רק לאחר זמן אומץ נוסח אשכנז, שאנו מתפללים בו היום. מתפללים שאחזו בנוסח ספרד ולא הסכימו לוותר, עברו לבית הכנסת הסמוך של החסידים ואפשר שאף ייסדוהו. לעומת זאת מנהגים וסדרים שהונהגו מיד בתחילה בוטלו לאחר זמן קצר: כך למשל נקבע על ידי הרב הראשון של בית הכנסת (ושל השכונה), הרב עקיבא גרוס, שבחזרת הש"ץ אין לחזור פעמיים על אותה מילה. אולם סטיות מעיקרון זה נתגלו כבר בימים הנוראים של השנה הראשונה. את ההפטרה קראו כל המתפללים יחד. גם נוהג זה נתבטל, כמו גם הקריאה בתורה בליל שמחת תורה לאחר ההקפות. היו סדרים ומנהגים ששונו ו\או נתבטלו רק בשלבים מאוחרים יותר, כמו למשל, עריכת קידוש בליל שבת והבדלה עם צאת השבת, לשמחת הילדים הקטנים שחגגו על היין. או, בתחום שונה לחלוטין, "התפרקות" במוסף של שמחת תורה עת נהגו לחמוד לצון על חשבון הש"ץ בחזרת הש"ץ: קשרו את כפות רגליו; הניחו קערה מלאה במים מאחורי רגליו כדי שיתקל בה בסיום התפילה; מתפללים "סייעו" לו בתפילה בקול ועוד כהנה וכהנה, והכל בניצוחו של ה"לץ" הראשי של בית הכנסת דוד טסלר (דוד פסק להתלוצץ, לתמיד, כאשר בנו, אליעזר, נהרג במלחמת יום הכיפורים). המנהג לומר את כל הקינות הכתובות בספר הקינות בבוקר ט' באב נשמר בקפדנות שנים רבות עד שהוחלט לצמצם באופן דרסטי את מספרן. גם בזמני התפילות ובמספר המניינים חלו שינויים רבים, אולם גם באלה רק לאחר שנים.

תחילה קבעו המייסדים את תפילת שחרית בחול בשעה 6:00 ובשבת ב 7:30. מניינים נוספים לא היו. השקט במהלך התפילה נשמר בדרך כלל, לא רק בשל המשמעת העצמית של המתפללים (שהיתה!), אלא גם בשל אדיקותה לעניין של אם אחד המייסדים (חנוך ארנטרוי הכהן), שהעירה לנשים ולגברים כאחד, בתקיפות רבה, וכולם נשמעו לה… מה שלא בוטל ונשמר בקפדנות שנים רבות היו הנוסח וניגוני התפילות. אלה נקבעו על ידי החזן הראשי הראשון אלכסנדר הולנדר, חזן משכמו ומעלה, שהטביע את חותמו על עולם התפילה של בית הכנסת עשרות בשנים. ניגוניו הושמעו זמן רב גם לאחר שנאלץ לעזוב את השכונה לעת זקנה, על ידי יצחק הרצוג וש"צים אחרים שהושפעו רבות ממנו. "התחרה" בו רק ישראל יערי (וולדמן), ממייסדי בית הכנסת, לא באיכות התפילה אלא בשל תכונה אחרת שרבים מהמתפללים אהבו: מהירות. יערי ידע לסיים את תפילת השבת בפחות משעתיים.

עולם התורה

עולם התורה לא היה עשיר. הוא לא השכיל להמריא חרף רצון המתפללים, שחלקם כאמור היו יודעי ספר ובני תורה. רצון להתכנס וללמוד במסגרות קבועות היה קיים, אולם הביצוע היה רופף. כבר בימים הראשונים החליטו המתפללים, שכל אחד מהם ילמד בכוחות עצמו אחת ממסכתות הבבלי. הגמרות חולקו בין המתפללים וגם הוחזרו לאחר זמן. לא ברור מה היתה מידת התועלת שהפיקו הלומדים מיוזמה זו. מכל מקום פעילות מסוג זה לא נשנתה. דרשות ושיעורים לכלל הציבור ניתנו במשורה. רבה הראשון של השכונה לא התפלל בבית הכנסת שלנו. הוא הקים מנין קטן בביתו ומשם סיפק את הצרכים הדתיים. עם זאת דרשות בפרשת השבוע התקיימו בלילות שבת. במיוחד זכורים לטוב בתחום זה שלמה גולדשמידט, איש חינוך מוערך וידען עצום של תקופת המקרא, וכן אליעזר ליפא לביא (יזכירוביץ'), מעובדיו הבכירים של משרד הדתות, תלמיד חכם מובהק שדרשותיו ריתקו את ציבור המתפללים, למרות העייפות שפקדה (ופוקדת) מתפללים רבים בשעה זו… אולם גם דרשות אלה פסקו לאחר שאליעזר ליפא עבר, בשל עלבון כלשהוא, לבית הכנסת של החסידים. רק בשנות הששים, עת נכנס לכהונתו רבה השני של השכונה, הרב אברהם דב אויערבך, תלמיד חכם אדיר בעל כושר רטורי נדיר, חלה התעוררות רבה בתחום התורני והחברתי, בשל אישיותו הדינמית ומעורבותו בחיי הקהילה. הוא היה גם החלוץ במתן שיעור שבועי לנשים, חרף התנגדותם של מתפללים לא מעטים.

הניהול השוטף

הניהול השוטף של בית הכנסת היה מרוכז בשנותיו הראשונות בידי גבאי אחד כשלידו עזרו בעצה ובביצוע קומץ מתפללים בעלי השפעה (דוד גרינוולד, שלמה גולדשמידט, ישראל מנחם גנץ, יצחק גלזנר, אליעזר ליפא יזכירוביץ', אלכסנדר הולנדר, ישראל יערי, משה ליכנטנשטיין, אברהם זליגמן – לא כולם בו זמנית, ואפשר שנשמטו מזכרוני מספר מתפללים). הגבאי הראשון יצחק שפירו, יוצא גרמניה, קבע במידה רבה את היסודות לפיהם התנהלו חיי בית הכנסת בימיו הראשונים. פעילותו חרגה לעתים מן השגרה במקוריות וביצירתיות. כך למשל ארגן במוצאי שמחת תורה של השנה הראשונה (ואולי השניה) הקפות שניות בליווי תזמורת בחצר בית הכנסת וברחוב – אירוע שלא נשנה עוד. אולם אופיו הסוער למדי גרם לעתים לחיכוכים מיותרים לפי כל קנה מידה. כך למשל קשה לשכוח את התקרית הקולנית, שנתרחשה לפני תפילת "כל נדרי", כאשר הגיע לבית הכנסת מתפלל אורח בנעלי עור… אישיותו המורכבת הביאה לבסוף לעזיבתו את בית הכנסת ואת השכונה, וזאת כעבור שנה\שנתיים בלבד. את מקומו כגבאי ירש יהודה סמואל, יוצא הונגריה, ששכל בתקופת השואה את כל משפחתו למעט בת אחת. יהודי נמוך קומה וצנום זה, פקיד במשרד האוצר, שלט ביד רמה כעשרים שנה. כהונתו הצטיינה בתקיפות רבה שהיתה משולבת בעדינות ובהתחשבות. גורמים אופוזיציוניים ניסו לעתים לזנב בדרכו, אך ללא הצלחה מרובה. לידו סייע השמש ליפא קאיי שהיה אחראי על תחזוקה שוטפת, וגם על גביית כספי הנדרים בבתי הנודרים. הוא זכה לאריכות ימים מופלגת, אולי בשל חיבתו היתרה לטיפה המרה, ואפילו לכוהל 96%.

חיי החברה

חיי קהילה מחוץ למסגרת התפילה ולשיעורי תורה החלו להתפתח, למעשה, מראשית הקמתו של בית הכנסת. תחום העזרה לזולת תפס מקום מרכזי בפעילות זו. זמן קצר לאחר הקמת בית הכנסת נוסד גמ"ח צנוע במימדיו, כמדומני על ידי ישראל מנחם גנץ ודוד גרינוולד. אף שסכומי ההלוואות היו נמוכים, לא מעטים נזקקו להם. השידרוג באפשרויות התמיכה חל שנים אחדות לאחר מכן כאשר ייסדו דבורה ויעקב ספירשטיין, זוג ניצולי שואה חשוכי ילדים, את גמ"ח "קרן יושר". מוסד זה ניצב במוקד העזרה לזולת במשך שנים רבות, ופעילותו המבורכת עדיין זכורה למתפללים הוותיקים.

העזרה לזולת היוותה לכאורה סימן היכר מובהק לקיומה של אחווה ושיתוף, והתקבל הרושם ש "כולם הינם חברים של כולם" – ולא היא. קשרים חברתיים של ממש היו מפותחים רק בחלקם. אלה התקיימו רק בחלק מהמשפחות יוצאות צ'כוסלובקיה והונגריה. בנוסף שררו יחסי שכנות טובים, ולעתים טובים מאוד, בקרב משפחות רבות של עובדי משרד הדתות.

כאן המקום לציין שגם בבית הכנסת שלנו, כבבתי כנסת אחרים, שררה התפיסה שלחשובי הקהל "מגיע יותר". קומץ מתפללים ברי השפעה זכו ברבים מבין הכיבודים האפשריים: עליות "נחשבות" לתורה, חתנים בשמחת תורה ועוד כיוצא באלה. בהקשר זה חרוט בזיכרוני אירוע המקפל בחובו את ההבל שבגינונים אלה ודומיהם. ימים אחדים לפני חג הסוכות של אחת השנים הראשונות, הופתעו המתפללים לראות מתקנים מיוחדים לארבעת המינים שהוצבו במקומות הישיבה של אחדים מחבריהם, כדי להקל עליהם בהחזקתם של אלה במהלך התפילה. מאחר שהמתקנים היו עשויים מחומר מאיכות נמוכה הם התפרקו זמן קצר לאחר התקנתם. המתפללים האחרים לא הצטערו על כך יתר על המידה…

לעתים לא נעדרו מתחים בין הגבאות ל "אופוזיציה" ובין המתפללים בינם לבין עצמם ואפילו בדברים פעוטים שגרמו ל "מלחמות-עולם" כמו, למשל, סגירת חלון ופתיחתו בעונת החורף. נדידה של "נעלבים" מבית הכנסת שלנו לבית הכנסת של החסידים (וחזרה) לא היתה תופעה יוצאת דופן. לחלק מההתנצחויות הללו היו גם צדדים חיוביים שכן הן היוו גורם מאיץ ומדרבן לחידוש, לרענון ולהתפתחות בחיי בית הכנסת.

שנות השמונים – המפנה

בשנות השמונים, ואפשר שאפילו זמן קצר עוד קודם לכן, חלה נסיגה בהתפתחות בית הכנסת. המתפללים התמעטו הן בשל ההסתלקות האיטית של דור המייסדים, והן מכיוון שכמעט כל צאצאיהם עזבו את השכונה ופנו איש איש לדרכו. די אם נציין להמחשת הדברים, כי בליל שמחת תורה היו מתפללים שזכו בשתי הקפות עקב מיעוט המשתתפים. נשקפה סכנה גדולה לעתיד. אלא שאז חל המפנה הגדול. בשלהי שנות השמונים ובראשית שנות התשעים החל להגיע דור חדש, שהיה מורכב ברובו מצעירים עולים חדשים יוצאי צפון אמריקה ומערב אירופה. הדור הזה השכיל להתחבר למורשת הראשונים, לכבד ולהמשיך את פועלם, ובו זמנית גם ליצור תבניות חדשות משלו. הוא יצק לתוכן תכנים רוחניים וגשמיים, שלא זו בלבד שלא סתרו במהותם את אלה הקודמים, אלא שהוסיפו להם רעננות והתחדשות. התכנים החדשים בשילובם של אלה הראשונים הביאו את בית הכנסת שלנו למתכונתו הנוכחית; אלא שזהו כבר סיפור המשך, שמן הראוי להעלותו על הכתב בהזדמנות הראשונה.

תיאור הדברים מבוסס בעיקר על זיכרונותיי, זיכרונות ילד שהגיע לשכונת בקעה במחצית הראשונה של שנת 1949, ושהחל להתפלל בבית הכנסת מיד עם הקמתו. לפיכך אין לראות בתיאור מסמך היסטורי מדויק ומלא. קרוב לוודאי שפרטים לא מעטים נשמטו ואחרים שהובאו אינם בהכרח מדויקים. עם זאת דומני שרוח הדברים והאווירה המתוארים מאפשרים לקבל מושג, ואף למעלה מזה, על תולדותיו של בית הכנסת בשנותיו הראשונות ועד לראשית שנות ה 60.

The History of Bet Knesset Emek Refaim: The Early Years

By Meir Edelstein, Kislev 5773.

Translated by David Olivestone

The circumstances surrounding the founding and the growth of our synagogue in its early years parallel, when looked at from certain vantage points, the history of the establishment of Israel and its early evolution. The observer will discern similarities with any difficult beginnings, coping with stubborn determination, while keeping an eye on the goal—in this case with constant struggles in all areas of life such as absorption of immigrants, harsh economic conditions, and social and cultural disparities, coupled with the emotional impact of our recent history, and so on.

What then, is it in this little world of ours—the members of our shul— that recalls for us the early years of the state?

The Baka Neighborhood in the Period Prior to the War of Independence

Clearly, the history of the shul is bound up with the history of Baka. The neighborhood, in which the first houses were built in the middle of the 19th century, was part of the creeping urbanization that began to take hold in the area of Emek Refaim (the German Colony and Greek Colony of today). Since the beginning of that century, mostly Germans (Templers) and Greeks had settled there. There are indeed records of attempts by Jews to purchase real estate there at the dawn of the 20th century, but these attempts had no impact on the development of the neighborhood.

The growth of Baka was gradual, with its first houses being built on Shimshon and Reuven Streets. By the end of the First World War, there were about 20 houses, among them the structure of our synagogue. It later expanded greatly to the boundaries that we see today. It would seem that the main factor in this expansion was the great availability of unoccupied fertile land, land which was inviting to prosperous Arabs and Christians, to Greeks and Armenians, and also to a few Jewish families. Most of these Jewish families left in 1929, apparently because of the events (the riots) of that year. Two families remained: the Saltzmans (owners of a factory producing metal products, among them the famous “blue boxes” of the JNF), and the Katzes. The neighborhood also attracted well-known and wealthy families, such as the main importer of Buick cars in the Middle East, who lived on the upper part of Rechov Shimshon, as well as senior British officials, amongst whom apparently was Edward Keith-Roach, the governor of the Jerusalem district under the mandate (1926-1945), who also lived on Rechov Shimshon for part of the time when he held that office.

The expansion and the prosperity came to a halt with the outbreak of the War of Independence. The Arab families fled during the first half of 1948, leaving behind them attractive houses with blossoming gardens. Some Christian families of Greek or Armenian descent remained in the neighborhood, as well as the two Jewish families (although the wives in these two families were Christian).

The Early Days of the State

The Haganah, which took control of the neighborhood without a fight during late April/early May 1948, closed it off to public access, and declared it a restricted military area, apparently out of some security concerns. Apart from the Haganah and the few residents who had continued to live in the neighborhood since the days of the Mandate, the area remained closed for several months to the entry of any new residents. Naturally, the abandonment began to leave its mark on everything. The houses became neglected and were sometimes deliberately vandalized, with their contents looted. Basic components were missing or broken, the electricity supply was frequently cut off, the supply of water was disrupted (a common Jerusalem problem in those times)—all these problems were commonplace. This summarizes the impressions of Walter Eytan, the first Director General of the Israeli Foreign Ministry, who visited the valley at that time and went into one of the houses in the neighborhood, accompanied by the U.S. Consul General, at the request of the latter: “Every room was gutted . . . the whole place looked like a horde of savages had passed through. It was not just a question of simple theft, but of deliberate and meaningless destruction,” and this is just one of many examples. Neglect was evident on the streets in terms of defective lighting, cut wires, sanitary conditions which were far from satisfactory, and other conditions.

Great waves of immigration came into the country following its founding, to which were added evacuees from the Jewish Quarter of the Old City, officials of government agencies who had to change their place of residence to Jerusalem, and others—all of which forced the government to open Baka for residential use in early 1949, or it may even have been a short time before that. The neighborhood quickly filled with people who made themselves at home in the abandoned apartments. Since government policy was not clear enough, some occupied the apartments by force, even invading apartments where people were already living. The term “invasion” was very common in those days, and occasionally the intervention of the police was necessary to restore order. In the end, quite a few homes were occupied by two families and sometimes even more. Theft of property was still common (a plague from which the neighborhood residents were freed only some years later).

The population was heterogeneous in every respect imagineable: Sephardi immigrants who had begun to arrive from Arab countries and from North Africa, alongside people from Central and Eastern Europe, to whom were added refugees from Germany, as well as native-born Israelis. There were, however, no Anglo-Saxon residents at this time. A mix of languages hovered in the air, with Arabic predominant over the others—Hungarian, Yiddish and Hebrew—I think in that order. It goes without saying that each community brought with it its way of life and cultural heritage. In short, a melting pot, in the full sense of the word, bubbled for many years until it could reach, more or less, its destiny.

The Establishment of the Synagogue and the Early Stages of its Development

These were the circumstances in which the first members of our synagogue arrived. The founders came mostly from Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Romania, with some also from Germany or Poland, and even one family born in the country. Despite the relative diversity of their countries of origin, they (almost) all had one thing in common: they were Holocaust survivors who had escaped the inferno by the skin of their teeth. Several of them had reached Israel even before the outbreak of World War II, but most of them came after it was over. Everyone left behind many family members in the killing fields, whose memory remained in their hearts at all times. Such remembrances and heavy hearts were part and parcel of our synagogue and floated in the air for many years. There were those—like David (Ziggy) Steiner—whose memories and emotional involvement would never leave them until their own deaths.

The founding families, about twenty in number, came to the valley either from other neighborhoods in the city or from other places. Almost all of them, and maybe all, were quite poor. They obtained their apartments by paying “key money” to the Abandoned Property Authority (later the Amidar Company). The heads of families were often clerks (especially in the Ministry of Religions), but there were also teachers, laborers, two writers, three lawyers and one doctor. It should be noted that most of them were learned and knowledgeable in Torah, and there were also some real talmidei chachamim (scholars). Although they did not come to the neighborhood as a group, many of them knew already each other from their country of origin or from the workplace. It made sense, therefore, that they wanted to establish their own synagogue. But the question was, where? The acute housing shortage in the neighborhood also affected the availability of public buildings. The requests that piled up during 1949 on the desk of the Interior Ministry’s Jerusalem District Commissioner for the allocation of structures for institutions, including for synagogues, are testimony to that. Therefore, in the first few months after their arrival in the neighborhood, they had to find places to daven wherever they could. The dim memories of the first congregants and their children suggest that they initially davened in the house of the first gabbai, on Rechov Ehud, right near the current building.

There are also those who remember that previously they davened in another shul in Rechov Gideon, and it is possible that each of these recollections is true. All along, some of them were trying to locate an available building. The opportunity came during the summer when they happened to notice an abandoned, locked building on Rechov Yael. It soon became apparent that the building had been used as a workshop and as the home of an Arab tanner who had abandoned the place, leaving behind a large collection of hides in the basement. So a building had indeed been found, but how could they get it assigned to them? They approached the District Commissioner on July 26, 1949 and waited for his response. Or did they? There is reason to believe that some of the founders (Yitzchak, a son of Eliyahu Levanon, Shlomo Goldschmidt, Moshe Lichtenstein, and Yisrael Menachem Gantz) took the law into their own hands and broke in there in the middle of the night. Only afterwards, when they had established themselves there, did they write to the Commissioner to obtain formal permission. In order to make it somehow legal, since it was possible that they could have been peremptorily evicted, they assigned one room (later part of the ezrat nashim), to the Ministry of Religions. The Ministry brought in various sifrei kodesh, and allocated one corner to a sofer (Torah scribe) to check and repair Torah scrolls which had been brought from decimated communities in Europe. In connection with this initiative, it is necessary to single out Eliyahu Levanon, Assistant Director General of the Ministry of Religions (two of whose sons, Yaakov and Moshe, had been killed just a year previously in the War of Independence), and Asher Edelstein, manager of the maintenance and storage facilities of the Ministry.

On the other hand, it may be true that it was only after obtaining the Commissioner’s approval that they entered the building. But if that were the case why did they need to break in in the middle of the night ? In any event, since we have many accounts that they were already davening there on Erev Rosh Hashanah 5710 (September 23, 1949), it can be determined that the synagogue was established somewhere between the end of June and the middle of September 1949. The structure corresponded, more or less, to the needs of the synagogue as it related to the men’s section, which consisted of a bright and spacious rectangular hall. What was amazing was that in the center of the north wall was a niche and within it an ornate wooden armoire (wardrobe) which had apparently been used by the previous tenants. Overnight, after some minor adjustments, this cabinet became a beautiful aron kodesh (ark); it seemed as if this piece of furniture had somehow waited for decades to fulfil its true destiny and purpose.

The arrangement for the women’s section was less felicitous. It was not possible to allocate a place behind the men's section as is usually done, due to the presence of another facility (the hasidic synagogue) at the southern wall of the synagogue. Therefore, it had to be located in two rooms in front of the men’s section on the north side of the shul. These rooms were connected by a door. Each room also had another opening that led to the men’s section. Between these two openings was the part of the northern wall where the aron kodesh stood. Due to this strange set-up, the women’s section was far from satisfactory, especially because of the very limited field of view into the men’s section and the overcrowding. It should be noted here that only one room of the two functioned as the women’s section all-year-round. The second room was actually part of the home of one of the members of the community which adjoined the synagogue on the north side. This room was used by the women only on the High Holidays.

There were other notable deficiencies: the front courtyard of the synagogue was neglected and unpaved. It was necessary to wait another fifteen years before it was renovated and paved by the Gantz family in memory of their father, Yisrael Menachem, who passed away while still in the prime of his life. The bathrooms (and kitchenette) did not exist, as such. There were some kind of facilities in the back yard of the synagogue, but these were hardly fit for human beings. It was only many years later that real bathroom facilities were installed in the front courtyard. One can still hear echos of the synagogue veterans’ sighs of relief when the new facilities were built. This drawing will facilitate an understanding of how the building appeared during the early years:

After its establishment, it was immediately apparent that the synagogue had to be equipped with all the various ritual objects and other necessary materials. With no financial resources, the founders were forced to use their ability to be improvisational and even gutsy. Furniture was brought in from wherever it could be found. For example, alongside the red armchairs and sofa which were found inside the building itself, bus and truck seats that the members dismantled themselves were brought over from the nearby Allenby Camp. Even so, some of those present were still forced to stand or sit on the floor during the services, due to the shortage of seats. Later, probably in the early fifties, some synagogue furniture was purchased from another synagogue that had bought new for themselves. Apart from some small alterations, they made no significant changes in the structure itself. In effect, the founders left the aesthetic development for the next generation, a generation that actually fulfilled its role in an impressive way. (Presumably, a way will still be found in an appropriate framework to describe the saga of the renovation of the synagogue, which actually began in the late eighties of the last century and which at the end of the process gave rise to the form of the building and its contents as they appear today.)

Equipping the shul with Torah scrolls and sifrei kodesh was somewhat easier. Three smaller Torah scrolls that had survived the Shoah were brought in by three members (David Greenwald, Shlomo (Fritz) Goldschmidt and David (Ziggy) Steiner), to which was later added a larger Sefer Torah, also “a brand plucked from the fire”, provided by the Ministry of Religions through the good offices of Asher Edelstein. The Ministry also provided chumashim, siddurim, machzorim, and other sifrei kodesh.

Liturgy and Customs

With all the importance of the physical set-up, the weighty questions really focused on the spiritual realm. The founders were faced, immediately, with questions related to determining the shul’s character, what type of content to fill it with, how to build the structure of the tefillot, and what would be the nature of the community.

As congregants sought naturally to preserve the customs of their forebears, and since most of the founders had been counted among the Religious Zionist camp in their European places of origin, the tefillot were generally conducted in the traditions and customs of those countries. But there were discussions that resulted in compromises. It appears that from the outset most of the founders chose to daven in Nusach Ashkenaz. However, there is some evidence that this was not decided on immediately, and that in those early days the chazan could daven in whatever nusach he was used to, including Nusach haGra and Nusach Sfard. Only after some time was Nusach Ashkenaz adopted, as we daven today. Those congregants who davened Nusach Sfard, and who didn’t want to give it up, moved to the Hasidic shul next door, and it may well that it was they who established it.

Conversely, there were some minhagim that were initially introduced but were changed after a short while; for example, it had been determined by the first rabbi of the synagogue (and the neighborhood), Rabbi Akiva Gross, that in the repetition of the amidah, no words could be repeated. However, deviations from this principle were already apparent during the High Holidays in the first year. Originally, the haftarah was read by all the congregation together, but this practice was stopped, as was reading from the Torah on the night of Simchat Torah after the hakafot.

There were also minhagim that were modified and\or were abolished only at a later stage, such as reciting kiddush in shul on Friday night and havdalah on Motza’ei Shabbat, to the delight of the small children who enjoyed tasting the wine. Or, in a completely different area, the “total collapse” of musaf on Simchat Torah, when they used to play jokes on the chazan during the repetition: they tied his feet together; they put a bowl full of water behind his feet so that he would fall over it at the end of the tefillah; the congregants would “help” him along in his davening in loud voices; and so on, all under the direction of the synagogue’s main “letz” (clown), David Tessler (David’s joking unfortunately came to an end when his son, Eliezer, was killed in the Yom Kippur War). The practice of reciting the entire book of Kinot on the morning of Tisha B’Av was strictly maintained for many years until it was decided to drastically reduce their number. Finally, many changes were instituted in the times of the services and in the number of the daily minyanim, but these came only some years later.

Initially, the founders set the time for shacharit during the week at 6:00 am, and on Shabbat at 7:30 am. There were no other minyanim. In general, there was quiet during the services, not only because of the self-discipline of the congregation (and that really was the case!), but also because of the piety of one of the founders (Chanoch Ehrentreu Hakohen), who remonstrated with both men and women, very firmly, and everyone listened to him. . . . Something which was not abandoned but was maintained very strictly for many years was the nusach of the davening and the tunes. These were set by the first chazan, Alexander Hollander, an outstanding cantor, who left his mark on the shul’s davening for decades to come. His melodies could be heard being sung—long after he was forced to leave the neighborhood due to his advanced age—by Yitzchak Herzog and other chazanim, who were greatly influenced by him. His only match was Yisrael Yaari (Waldman), one of the founders of the shul, not in the quality of his davening but because of another quality that many congregants loved: speed. Yaari knew how to finish the Shabbat service in less than two hours.

The World of Torah

The world of Torah was not rich. It failed to take off despite the desire of the congregants, some of whom, as we noted, were knowledgeable and steeped in Torah. There was a desire to come together and learn at fixed times, but in practice this was sporadic. Already in the early days, the members decided that each one would learn on his own one of the tractates of the Babylonian Talmud. The gemarot were distributed and after a while were returned. It is unclear how much they got out of this initiative. In any case, this kind of program was not repeated.

Drashot and classes for the general public were limited. The first rabbi of the neighborhood did not daven in our shul. He set up a small minyan in his home and from there supplied the area’s religious needs. Still, drashot on the parsha of the week were given on Friday nights. Especially remembered in this connection is Shlomo Goldschmidt, a valued educator and great scholar of the era of the Tanach, and also Eliezer Lipa Lavie (Izakerovich), one of the senior executives of the Ministry of Religions, a brilliant scholar whose sermons fascinated the crowd, despite the fatigue that seemed to affect (and affects) many congregants at this point. But even these sermons ended after Eliezer Lipa moved, due to some insult or other, to the shul of the hasidim. Only in the sixties, when the second rabbi of the neighborhood, Rabbi Avraham Dov Auerbach, a tremendous scholar with a rare rhetorical ability, took up office, was there a great awakening in Torah learning and social activities, due to his dynamic character and involvement in community life. He was also a pioneer in giving a weekly shiur for women, despite the opposition of not a few members.

Routine Management

The day-to-day management of the synagogue was concentrated in its early years in the hands of one gabbai, who was assisted by a small group of influential congregants (David Greenwald, Shlomo Goldschmidt, Yisrael Menachem Gantz, Yitzchak Glasner, Eliezer Lipa Izakerovich, Alexander Hollander, Yisrael Yaari, Moses Lichtenstein, Avraham Seligman—not all at the same time, and perhaps the names of a few others have slipped from my memory). The first gabbai, Yitzchak Shapiro, who stemmed from Germany, largely determined how the shul was run in those days. The way he did things sometimes deviated from the routine because of his originality and creativity. For example, on the night following Simchat Torah in the first year (and perhaps also in the second) he organized hakafot shniyot with an orchestra in the courtyard of the synagogue and in the street, an event that was not repeated. But his rather excitable nature sometimes caused unnecessary friction. For example, it is hard to forget the loud incident before the Kol Nidrei prayer when a visitor showed up at the shul wearing leather shoes. His difficult personality eventually led to his leaving the synagogue and the neighborhood after just one or two years. His place as gabbai was taken over by Yehuda Samuel, of Hungarian descent, who had lost his entire family in the Holocaust with the exception of one daughter. This short, slight individual, an official in the Ministry of Finance, lorded it over the shul for twenty years. His tenure was distinguished by his firm manner which was combined with politeness and sensitivity. A few naysayers sometimes tried to trip him up, but without much success. He was helped by Lipa Kay, who acted as shamash, and who was also responsible for the daily maintenance, as well as the collection of pledges. He enjoyed extreme longevity, perhaps due to his great fondness for the bottle, including even “sechs und neinziger” (96% proof alcohol)!

Social Life

Social life, beyond the framework of prayer and Torah classes, began to develop, in fact, with the beginning of the establishment of the synagogue. Helping others was foremost in this area. Shortly after the establishment of the synagogue, a modest charitable fund, was set up by, I believe, Yisrael Menachem Gantz and David Greenwald. Although the amounts loaned were small, quite a few people needed them. An increase in the available funds was made possible a few years later when Devorah and Yaakov Saperstein, a survivor couple with no children, established the “Keren Yosher” fund. This fund was the focus of helping others for many years, and some veteran members still remember its sacred work.

Concern for others was seemingly the basis of an air of brotherhood and cooperation, and there was an impression of “all for one and one for all”, but it was not actually so. Genuine social relationships were only somewhat developed among some of the families who came from Czechoslovakia and Hungary. In addition, good neighborly relations—indeed sometimes very good—prevailed among the many families of the employees of the Ministry of Religions.

It should be noted that in our shul, as in many others, there was a perception that the more prominent people deserved preferential treatment. A handful of influential members received most of the preferred honors: the more significant aliyot, the chatanim on Simchat Torah and the like. In this context, etched in my memory is an event which reflects the nonsense of this type of behavior. A few days before Sukkot in one of the first years, congregants were surprised to see that special lulav holders had been installed for certain members, to make it easier for them to hold the lulav and etrog during davening. Since these contraptions were made of poor quality materials, they broke shortly after they had been put in. The other members were not too upset about that . . . .

Sometimes, the tension between the gabbaim and the “opposition” and among the members themselves could not be concealed, and even small things became “World Wars”, as, for example, opening and closing the windows in the winter. Roaming by the insulted parties between our shul and the shul of the hasidim (and back) was not uncommon. Some of these incidents also had their positive side because they constituted a catalyst for renewal, for refreshing and developing the life of the synagogue.

The Eighties—A Turning Point

During the eighties, and perhaps even a short time before that, there was a slow down in the development of the synagogue. There were fewer people attending, possibly due to the gradual departure of the founders, or possibly because almost all of their descendants left the neighborhood and went their separate ways. It will suffice to illustrate things to record that on the night of Simchat Torah some of the men received two hakafot since there were so few of them present. There was a definite sense of crisis concerning the future. But then there was a major turning point. In the late eighties and early nineties a new generation began to arrive, made up largely of young immigrants from North America and Western Europe. This generation was able to connect to the heritage of the founders, to respect and to further what they had achieved, and at the same time to create new ways of their own. They were able to introduce more spiritual and material content, while not only not repudiating what had gone before them, but refreshing and renewing what was there. The integration of these new factors brought our synagogue to its present form; but this story continues, and should be put into writing at the earliest opportunity.

The description of these events is based for the most part on my memories, the recollections of a boy who came to the Baka neighborhood sometime in the first half of 1949, and began to daven in the synagogue immediately upon its establishment. Therefore, this should not be regarded as a definitive and complete historical document. Probably quite a few details have been omitted and others cited are not necessarily accurate. However, I believe that the spirit of things as described here will enable one to get at least a basic idea about the history of the synagogue from its early years and up to the start of its 60th year.

מאוד נהניתי לקרוא את ההיסטוריה של בית הכנסת. לאמיתו של דבר נקלעתי למאמר די באקרעי משום שחיפשתי מידע על פריץ גולדשמיט שאותו הכרתי בילדותי בגלל קשריו עם משפחות טרוייס והילדסהיימר. אשמח אם תוכלו לכווין אותי למשפחתו שכן אני עובדת על זכרונותיה של ג'ולי טרוויס שכותבת גם על פריץ בספרה (שאני מוציאה מחדש עבור צאצאים שלא הכירו אותה ).

בתודה

Dr. Debbie Lifschitz

ירושלים

אגב, אני חושבת שכדאי להוסיף שמות לתמונות שמופיעות במאמר. לא כולם וכרים / מזהים את האנשים בתמונות.

:In this sentence in the English translation, do you mean 1948?

The Arab families

fled during the first half of 1949, leaving behind them attractive houses with blossoming gardens.